Last week Nintendo president Tatsumi Kimishima once again responded to the idea that the company might join in with the burgeoning VR arms race with a tepid ‘let’s wait and see’ — commenting that while Nintendo was studying VR, they had caution about the ability for users to “play for hours on end without problems”. However, patents uncovered in December last yearindicate that Nintendo have at least studied the idea well enough to come up with a potential product for it. And they’d be right to do so, because I believe Nintendo stands uniquely placed in the marketplace to provide the best, most accessible and cheapest full-VR experience, and to become the leader in the charge of bringing VR to the mainstream audience.

In my job, we’ve been working with VR since the earliest days of the Oculus Rift and I’ve been extremely fortunate to have been able to both witness the rapid development of what the technology is capable of, as well as to experiment with all the different varieties available. From these experiences, I believe we can categorise the various forms of VR into three specific levels, all three of which I believe Nintendo stands in a fairly unique position of being able to touch on: Full VR, Mobile VR and Non-Interactive VR.

Full VR

This is effectively ‘true’ Virtual Reality. For this type of VR, the Head Mounted Display (HMD) will typically have a series of sensors on it and as such will utilise multiple sensors to track its position as well as the positioning of one or more (though ideally one for each hand) motion controllers that gives you the feeling of genuine presence within the virtual world as the movement of your head and hands translates to actions of your digital avatar. This is the VR employed (to varying levels) by the Oculus Rift, the HTC Vive and Sony’s Playstation VR.

The other things that all existing examples of this form of VR have is that they are all pretty expensive and require a lot of set up. The Oculus Rift and HTC Vive are both pretty expensive bits of kit by themselves (roughly an equal outlay of about £800 once you include the Oculus’ touch controllers — which you absolutely should) and to run them you will need a fairly powerful PC of roughly the same price or better.

The PSVR provides a much cheaper alternative at £349.99 on its own, but as well as the PS4 itself (between £230-£350 depending on whether you get a PS4 Slim or PS4 Pro), you also have to separately buy the Playstation Camera (required) and the Playstation Move Controllers (optional — but recommended for true ‘Full VR’). This makes your minimum outlay from having none of the hardware closer to £700. It’s still cheaper than going all-in on the Oculus Rift or HTC Vive, but it’s crucially still too expensive to be truly considered a mainstream option. Even for existing PS4 owners, the cost of the PSVR, the Camera and the controllers contributes the lion’s share of that cost at over £400.

All three examples also require a considerable amount of setup before play and leave you with a lot of wires and expensive kit to tidy away afterwards. You have to sacrifice a lot of cost and convenience for these full VR experiences.

Typically, however, the sacrifice is worth it. Full VR — particularly the most capable examples of the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive — is a truly revolutionary experience for gaming. Third person games benefit from a wider feeling of vision and control, while first person games benefit the most by not only feeling truly immersive, but in giving you the ability to look around you naturally and restoring your peripheral vision it elevates the gaming experience in a way that simply isn’t possible without VR.

Mobile VR

There are two key examples of Mobile VR on the market today: the Samsung Gear VR; and Google’s Daydream VR – an open alternative to Samsung’s product that will no doubt be supported on most high-end Android phones in the future.

In Mobile VR, the kit itself is effectively just a plastic headset with lenses, and as a result is relatively inexpensive. The actual work is all done on your own mobile phone, which is attached/slotted into the HMD and displays two images on the screen — one for each eye — to provide the 3D virtual image for your brain. It’s effectively the same thing the Full VR HMDs do — but with all the processing taking place on your phone.

The great thing about Mobile VR is that most people already have a device full of motion sensors with a high resolution screen and as such the entry level is relatively low. There are downsides, however. Mobile processing is obviously not as capable as the high-end PCs are, so there are limits in just how much even the highest-end phones can render, especially as it has to render each frame twice. The greater accessibility of just requiring a cheap headset and your phone also reduces the actual ability to interact with experiences. The only available input for the Samsung Gear VR is a touch-panel on the side of the HMD, which can quickly get uncomfortable for long term use in a game. Google’s Daydream View does come with a motion-controller remote, but as with the remote packaged with the Oculus Rift, its use is limited by there only being one of them and a lack of buttons. It’s also not easy to get around this issue without creating a fragmented user base, where a certain VR experience/game would require an additional accessory and thus more cost and inconvenience.

Overall, Mobile VR gives users a middle-ground VR option that is suitable for first experiences with VR, but games-wise, is more of a cheap imitation and a novelty. It should also be noted that while the HMDs themselves will usually be available for under £100, the phones themselves will all be high-end phones costing over £500+ off-contract, so the key benefit is once again really only if you have a phone that supports one of the two main platforms.

Non-Interactive VR

Non-Interactive VR is essentially just 360 degree video content. It might be pre-rendered, rendered live or even filmed using a 360 degree camera rig, but all the same, it is content that you view, albeit in a non-traditional manner, without interacting or affecting it. In 2017 this overwhelmingly makes up the bulk of VR content available, and while it’s available on both the Full VR kits as well as the mobile platforms, there is a piece of kit that’s become synonymous with this kind of content — the Google Cardboard VR.

Cardboard VR is the progenitor of Google’s Daydream VR. As well as a platform and API for the content, it’s also an openly available spec for making a low-cost headset (for example, out of cardboard, although so long as you match the positioning of the lenses to the specification you can make it out of anything at all). As a result of this openness, marketing agencies such as ours have been using it to create branded headsets that can be distributed to users to view their 360 degree content with. It’s the modern day equivalent of the holographic cards you used to get in a box of Corn Flakes. Just like Mobile VR, all it requires is the headset and your phone (and in Cardboard’s case, most phones will work, even iPhones) and as it’s non-interactive and typically non-intensive for the device, the downsides don’t really apply either.

As the name suggests, it’s the least capable of the VR experiences available, but it is by far the most numerous, the most accessible and the most likely to be used most often by mainstream users. These experiences are so important to the VR eco-system that they need to be a major consideration for all VR products, and the Cardboard platform and specification provides the cheapest current option for getting into the most numerous category of VR content.

Where the Nintendo Switch fits in

Where the Nintendo Switch fits in

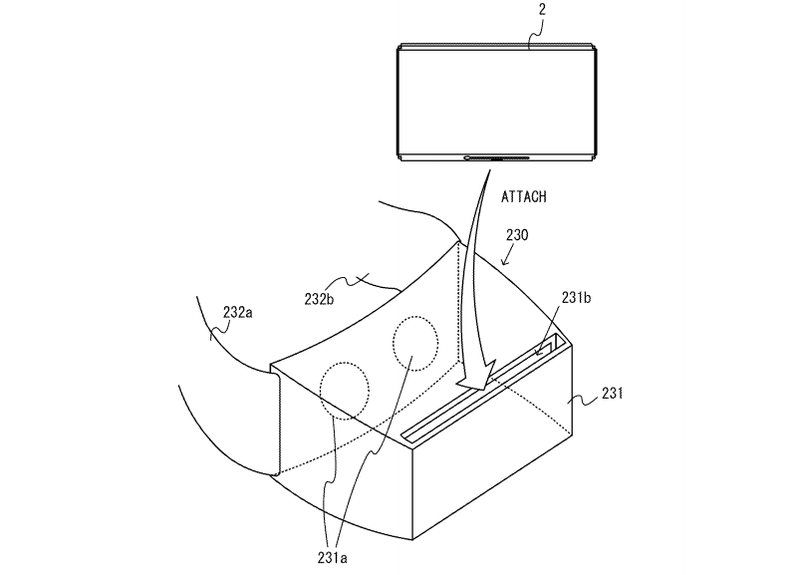

The key thing about the Nintendo Switch is that it really is a perfect device to target all three levels. At its core, it sits within the Mobile VR category as it is, itself, a mobile device that would do all the hard work while slotted into a presumably cheap headset.

Like Mobile VR, it does still have the downside of being underpowered compared to a high-end PC or a PS4, but compared to other examples of Mobile VR, it does at least have the power of a dedicated nVidia mobile GPU to back it up.

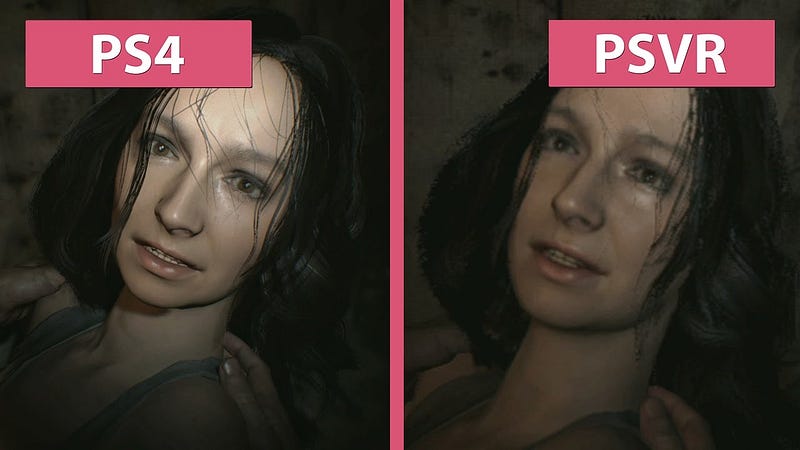

An important point about VR, though, is that the power required to output those visuals twice negatively affects all platforms graphically speaking. However, while those games will never look quite as good or quite as detailed in VR as they would in flat 1080p/4K, the added immersion and realistic field of view diminishes that concern by quite a lot in practice. As a result, the Samsung Gear VR’s output doesn’t look that far removed from what you can see in PSVR’s visuals — and neither detracts enough from the experience to weigh down the positives. The same would absolutely be true of the Nintendo Switch’s output.

Unlike other Mobile VR examples, however, the Nintendo Switch comes packaged with two motion controllers equipped with a full range of buttons. This places it in the unique position of being able to provide Full VR level input without requiring lots of new accessories. A sensor of some description would be required to be able to relatively place your controllers (and thus your hands) accurately, but this could be as simple as being integrated into the headset itself.

This level of control would allow Nintendo to develop VR experiences that would even rival Resident Evil 7’s VR mode, in giving you proper Full VR input for a fully featured game. Best of all, because the only additional accessory would be the HMD itself — developers could reliably develop a VR mode around the Joy-Con motion controllers without requiring, or even desiring, a fallback to a more traditional controller because the hardware cannot be guaranteed.

While you will undoubtedly find a better experience on a PC with an Oculus Rift or HTC Vive setup, the Switch would be the happy medium that neither the PSVR nor existing Mobile VR solutions truly fit into.

Crucially, however, the Switch would be the best priced proposition for a true representation of a VR experience. With the base hardware itself costing £280 and an HMD accessory likely ranging between £60 and £100, the all-in cost of around £350 for the hardware to get going from nothing at all is the best value option of all — and would manage to deliver a more complete VR experience than the next best value options of Cardboard and Mobile VR.

I would argue that if Nintendo could deliver a title for VR on the Switch that delivered the same instant and tactile appeal that Wii Sports delivered for the Wii, that it would easily cement the Switch’s position as leader in the charge for bringing VR to the masses. The inherent portability and shareability of the gameplay of the Switch would combine with the natural curiosity of trying something new and instantly engaging such that scenes like offices huddled around a set of desks while colleagues try a game like ARMS in VR would surely become common. And, much like the huge interest that similar scenes sparked for the Wii, the Switch would stand poised to see a great deal of success directly because — in comparison to the competition — it would be a huge bargain.

VR stands on the cusp of breaking through to the mainstream as people are developing wider understanding of what it means, both for consuming new types of content and for what it can bring to games. Resident Evil 7’s release and positive reception was a huge step towards legitimising it as a long-term experience, but the remaining barriers of hardware and cost are keeping it back from truly meeting its potential.

Nintendo bringing a VR accessory to the Switch would not necessarily be the peak of what we can achieve or experience with VR, but it could be the first truly accessible and affordable Full VR experience and that’s the spark the medium truly needs to catch on. Nintendo might be rightfully cautious about jumping into an unproven market, but, with the potential they have already in their hands, it’s definitely in the best interests of that market — and potentially Nintendo themselves — that they do so.